Weird Wednesday is a chance for us to dive into the stranger PC games that have been released over the last few decades. This week, we take a look at Weird Dreams, a surrealist adventure game exploring the feverish dreams of a young man named Steve. While the creators dreamed big, the game fell into the dustbins of obscurity.

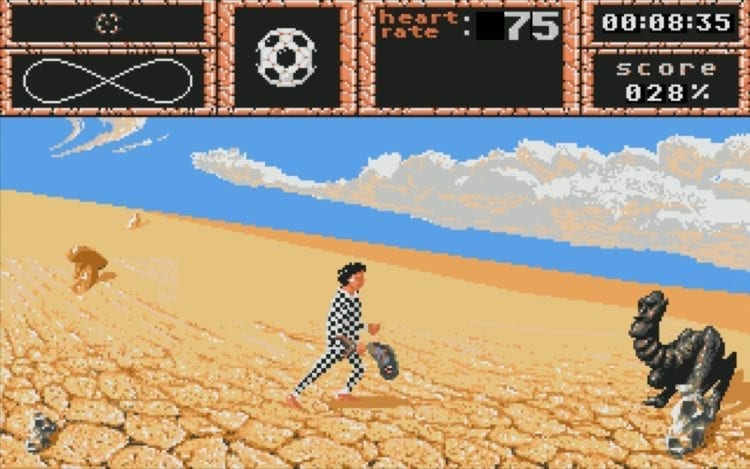

I wish there were a simple way to explain what this game is, but there’s not. While undergoing a surgical procedure, the main character of the game, Steve, dreams he is in a cotton candy machine. He fights a wasp, gathers orbs, throws a man-eating soccer ball at a knife-wielding child, slaps a foot-shaped demon with a fish, and eventually kills a giant brain.

I’ve personally had dreams that made less sense than this game, but they’re few and far between. The game follows dream logic; for example, desert areas may have extremely different enemies, but they all have fish to be used as weapons. Ultimately, the game has no story, and Steve wanders between demonic pianos and rose gardens searching for some way to escape these dreams.

Every Game Needs Lore

The developers must have known their game made no sense. They brought in Rupert Goodwins, a British writer and former technical editor for PC Magazine, to write a 64-page novella accompanying the game. In the novella, a demon named Zelloripus possesses Emily – the girlfriend of Weird Dream’s protagonist Steve – and gives Steve three mystical pills to help with his illness. Because Steve is a teenager growing up in the 80s, he takes the mysterious pills and, needless to say, has some bizarre dreams. The novella’s plot ends and the game begins with Steve on the operating table, being put under to fight for his life inside his nightmares.

As a prequel to the game, the novella feels over the top; the phrase “any chemist worth his NaCl” shows up on the second page, and Steve’s dentist acts as if a third set of teeth is a common occurrence. However, even with the cheesy writing, Rupert Goodwins manages to take the developers’ plot and make it interesting. The novella won’t show up in a college course, but I can imagine a teenager digging the story.

Unfortunately, the game itself doesn’t feel like it has a plot at all. Stages barely relate to each other, even in an abstract manner. The ending of the game shows Steve regaining his consciousness, but none of it deals with his demonic girlfriend Emily. If the novella and the game didn’t share the same name, there’d be no way to tell they were related at all.

Towards the end of production, Weird Dreams appeared on the British kids show Motormouth for several weeks. Testers complained that the game was too difficult, but despite the problems with the game, it released on various platforms throughout 1989 and 1990. Reviewers generally disliked the game. As Microprose absorbed the development company in a merger, the game largely fell into obscurity.

Why Did It Fail?

It’s easy to critique a game from the late 80s as being too strange. The gameplay is non-linear, the settings are abstract, and the monsters are, perhaps, a little suggestive in appearance. However, gamers had already been used to abstract concepts from that same decade. Often, systems limited graphics, and players grappled with obscure shapes that barely resembled characters at all. In fact, the industry often showered praise on the more unique ideas (as happened a decade later with Grim Fandango). The ideas in Weird Dreams could have used more polish, but the weirdness didn’t cause it to fail.

The difficulty did.

The game has one-hit deaths, no health bar, oversized hitboxes, unpredictable enemy movement, and death loops in certain areas, and the player only has five lives to finish it! While there’s an in-game cheat to get infinite lives, I died around 200 to 300 times by the end of my first full playthrough.

The biggest design crime, though, comes with control responsiveness. Every movement in the game takes several frames, and once you start moving, you’re committed. Even the act of turning around feels like a chore. Combine that with sporadic enemy movement, and the DOS version of the game is nearly unplayable. If anyone wants to attempt completing the game in five lives, be my guest.

Miss the light, and it’s supper time.

Other versions of the game on Commodore64 and Amiga ended up fixing some of the responsiveness issues. However, most of the world had moved on from those computers; IBM largely dominated the market with upgradable computers, extending their hardware lifespans for years.

Surrealism in Video Games

While the game largely failed, I still feel a unique charm from Weird Dreams. In 1989, other released games such as SimCity and Populous strove for realism; the games were new, but the worlds were familiar. Even fantasy games like Castlevania III or Phantasy Star II relied on established universes. Telecomsoft took a risk with Weird Dreams, and even if the man-eating Thanksgiving turkey didn’t generate sales, it was still original.

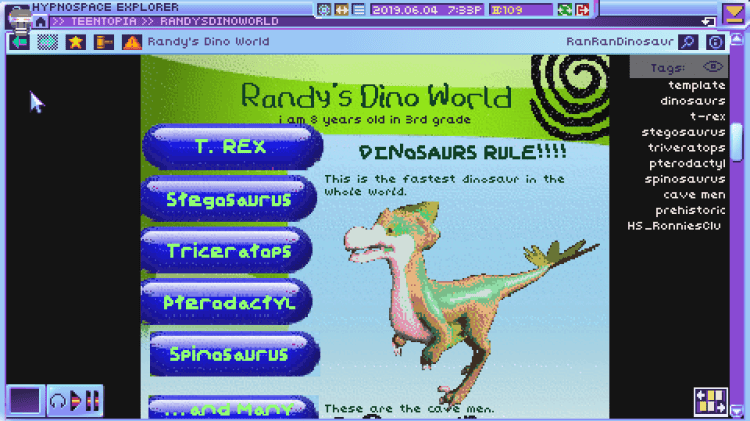

Even now, surrealism mostly remains with independent games, the most recent example being Hypnospace Outlaw. In the game, players explore a sleep-induced 90s internet community. Everything feels strange, exaggerated, yet familiar – a twist on a world that many of us explored in our childhood. Surrealism takes what is familiar to us and changes it, finding the strange in things we experience every day.

While Weird Dreams largely fails as a video game, it still manages to create a world where the familiar feels strange. It changes the rules, defies predictability, and overall challenges what video games have always been about. Risks definitely exist for unconventional storytelling, but the work is worth it when a developer finds that unique way to connect with a player. Not everyone will connect, but not everyone has to; the story is still worth telling.

Published: Jun 5, 2019 09:29 am