InXile’s decision to crowdfund a spiritual successor to Planescape: Torment was an expression of audacious ambition. Their Torment: Tides of Numenera may use a different setting and rule-set to the 1999 original (Monte Cook’s Numenera, as opposed to the D&D realm now owned by Wizards of the Coast), but the structure, presentation, and themes are specifically designed to evoke its celebrated RPG namesake. This is an extremely challenging path to walk, with the tar pits of nostalgic pandering and inferior re-telling awaiting any misstep.

There are some wobbles towards both of those precipitous drops throughout Torment: Tides of Numenera’s novel length, dimension-spanning tale. But while it clearly draws from similar ruminations on consciousness, morality, and individual power, there’s enough original thought here to set inXile’s release apart from its forebear. The tone is similar, the themes familiar (as universal classics of philosophy tend to be), yet the creative whole is largely distinct.

That’s in part thanks to the Ninth World setting, which encompasses people, places, and circumstances just as bizarre as the Planes of the original. Again, there are echoes of the previous Torment in the unusual civic rules of the city of Sagus Cliffs, and the consequences of a near-immortal being lost in the pursuit of knowledge above all other cost. This time, though, your own player character embodies one of those consequences.

In Torment: Tides of Numenera, you are the Last Castoff, a product of a being known as The Changing God who creates and discards body vessels as his consciousness hops between forms. Each of those discarded bodies forms a new consciousness when The Changing God departs, and yours begins to manifest as the body hurtles towards the ground at tremendous speed. Adding an extra metaphysical layer to the tale, your mind exists as an actual, labyrinthine space that can periodically (and usefully) be explored during death; recalling the benefits of exploiting your immortality in Planescape.

It’s a brilliant premise for an RPG. You’re dumped in a barely familiar city (Sagus Cliffs), a place literally built upon the strata of billions of years of forgotten history, with the mystery of your own birth and a dispassionate, elusive creator to confront.

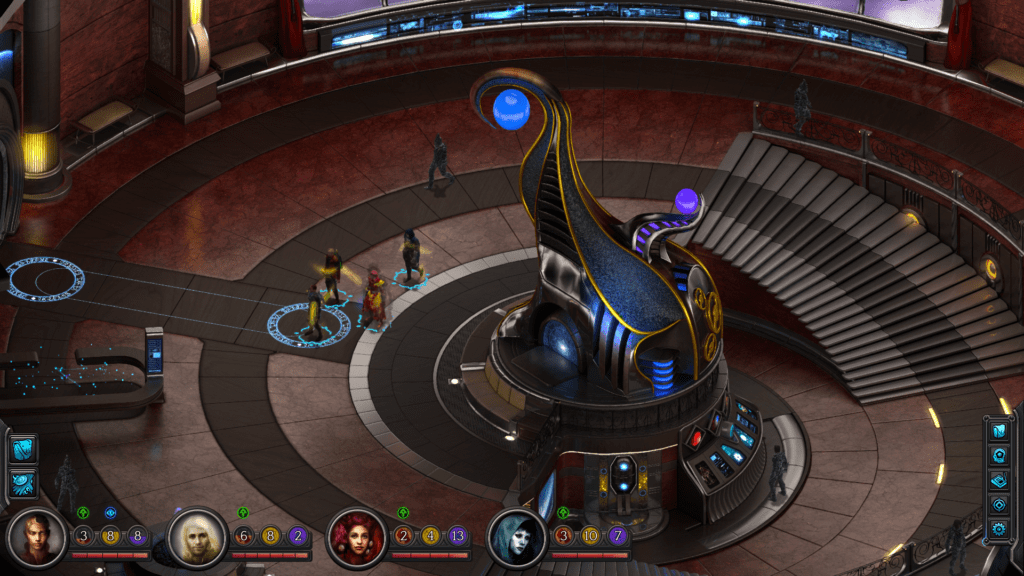

What follows is an ocean of reading to dive into. Just like its main source of inspiration, Torment: Tides of Numenera is overwhelmingly a game of text, dialogue choices, and even more text. It has the same wonderful isometric location ‘maps’ as Pillars of Eternity (and in fact seems to use Pillars techniques in their creation), rich in strange details like fountains of living, purple fish and fleshy, Hieronymus Bosch-like horrors; but much of the imagery is external, conjured by passages of text or choose-your-own-adventure style interludes.

There are periodic moments of turn-based combat too, their oft-avoidable nature neatly summarised by the terminology ascribed to them. In Numenera conflicts are not inevitable, grinding RPG encounters, they are, in every case, a ‘Crisis’.

As inXile have always stated, Crisis events are unique encounters. Each one has a definitive place in the story, and you’ll never just randomly run into a bunch of guys who want a fight. Many of these encounters are avoidable, but even the ones which are not have ways out that don’t involve slaying everybody in the room. There’s always an option to, say, sway a foe to your way of thinking with a dialogue check, or beat a hasty retreat. It’s not really accurate to say you can make it through the game without any combat whatsoever, but as long as your party are capable of a fighting escape they should be able to handle things.

If you do opt to go all-in on combat, Torment: Tides of Numenera is a relatively straightforward ‘one movement plus one action, or a longer movement’ turn based affair. Characters and foes have both melee and esotery (pretty much tech-magic) skills at their disposal, there are basic rules about weapon strengths vs armour, special attack types vs resistances, flanking, and so on. You also have access to (usually) one-time use gadgets called Cyphers, which are so powerful that each character can only carry a set amount at any given time (hold too many, and debuffs or even death await).

It’ll be mostly familiar stuff to anybody who’s played a turn based party strategy game before, but the lack of too much complexity keeps the battle encounters focused and tight.

After all, though it has plenty of cRPG trappings, Torment: Tides of Numenera is propelled far more by its writing than by any tactical combat mechanics or interconnected ability systems. That writing is strongest when the mythos of its world connects with a given quest-line, and when the sci-fi-medieval-cyberpunk setting (or however you want to classify it) uses its strangeness to make a point about recognisable, human traits.

Sagus Cliffs, for example, has a system of acquiring citizenship which demands that its participants literally give up one year of their life. That year of life takes semi-sentient, physical form as a Levy, who police the city for twelve months. Tides of Numenera is able to explore and expand on this intriguing concept through the city’s institutions (such as the Order of Truth whose machinery creates the Levies), and through specific quests.

One such mission has you dealing with a malfunctioning Levy, who has been mistakenly formed from a hypothetical year of life where the source basically suffers from a traumatic stress disorder. The presentation and ultimate resolution of that quest (and there are several ways to deal with it) manage to merge worldbuilding and personal dilemma in a truly elegant manner.

These moments are Torment: Tides of Numenera’s greatest achievements, and where it can match Planescape: Torment in narrative-based quest design. They don’t come as frequently or as consistently as in Planescape, but there are enough inspired sections in the game’s two main city ‘hub’ areas, and through certain companion story-lines, to sustain a real fascination with the setting and its people.

In Numenera’s weaker periods, though, the prose can slip into a purple hue and begin to drag. The weirdness of the Ninth World (and multiple other, ‘off-camera’ areas) is a boon to the story overall, but there are times when yet another memory digression into mysterious alien environments with challenging fantasy names starts to feel overwrought. Especially in cases where the recollection has, at best, fringe impact on the main story. Too much abstract transdimensional musing can make even the most mind-expanding concepts feel bland, and Tides of Numenera skirts that boundary a little too often.

Mechanically speaking, the game revolves around three core stats: Might, Speed, and Intellect. Attendant skills and abilities will improve speech or combat rolls to varying degrees (or degrade them, if you’re untrained in a given area), but those stat checks can generally be boosted by ‘spending’ points from your three main pools. If you’re attempting to nab an item from an NPC, for example, then your Quick Fingers ability will be the primary factor, but your odds can be much improved by using some extra Speed.

The three stat pool caps are increased through levelling up, and can be replenished by consumable objects and by sleeping. It seems designed with the intention to make spending your limited stat pools on speech or ability checks a difficult decision, but the ease with which you can replenish those pools (or dip into the pools of your party companions) means that with a bit of basic stat management you can actually pass almost every check you come across. Sleeping very, very rarely advances quests in a negative way (this happened to me once in the entire game), and is often either free or (once you’re a few hours in and have a little wealth) quite affordable. Consumable stat top-ups are also quite numerous.

The result is a central system which appears as if it wants to make you think twice about spending points from stat pools, and agonise over whether to retain your advantage for a more important event in future, but ends up strangely muted. That’s odd, because failing stat checks in Torment: Tides of Numenera can sometimes lead to interesting outcomes or guide players down alternative quest paths, so the developers need not have feared this consequence.

Those who’ve been following the development will know that Tides of Numenera has been subject to some late in the day cuts (or late in the day admission of cuts), and that may be emblematic of a deeper struggle to reconcile the game’s enviable ambition with available resources. Certainly, aspects like the Legacies are reduced from their original Kickstarter description. The Legacy of your character is still relevant, but it now amounts to an ongoing Tidal alignment which changes according to your actions, concluding with a rather superficial paragraph during the end game credits.

If sections of the main narrative had to be trimmed, however, Numenera covers it fairly well. The game’s two hubs (Sagus Cliffs and the grotesque, living Bloom) are joined by somewhat more linear connective tissue in the form of Valley of Dead Heroes (which also neatly serves as a crypt depository for Kickstarter backer names), and lead to a final, climactic stretch. Everything is wrapped up, and (barring, arguably, one companion) there are no sequel hooks. This isn’t a Tyranny-like situation where the game manages to conclude but also feel a bit like Part One. The end stretch is, however, a bit of an accelerated race to the finish. Threads are concluded and tied off, but in a way which suggests there may have been more extensive sequences planned.

By the end the in-game counter had me at around 26 hours. Progression in this title probably owes as much to reading speed as anything else though, meaning it’s not particularly easy to judge an average completion time. Review code came in early, so I was able to explore as many side avenues as possible in the play-through. Note also that I’d played all of the Sagus Cliffs area before, in the beta, so that area was all familiar and passed much quicker the second time around.

Given how many different outcomes can be attempted and achieved in some of the quests, it probably won’t surprise you to learn that Torment: Tides of Numenera has a lingering bug or two. It was rare, but sometimes dialogue options or responses seemed to react to information which hadn’t yet been revealed. At another point, I’m pretty sure my ‘Tidal Affinity’ skill temporarily vanished from my character sheet (awkward, because it’s useful), and only returned once the protagonist had gained another level.

The most irritating bug was also the strangest. My save seemed to get infected by a persistent noise best described as ‘electronic sparkling’ (belonging, I think, to one of the Ninth World’s pieces of esoteric machinery), which would only ever go away when another significant background sound effect over-rode it. Until that happened, each reload was either a sort of light audio torture or an invitation to play in silence for a bit.

On the more positive technical side of things, the game managed a firm 60fps throughout on my 380X (aside from one scene heavy with fire effects), and had acceptable loading times even on an HDD. As expected, perhaps, but after Pillars of Eternity at launch neither of those things can be taken for granted.

Taking on the mantle of an absolute classic of the PC RPG canon was always going to be ballsy move for inXile. Doing so absorbs a lot of the fondness for the Torment name (witness the success of the crowd-funding campaign), but also involves the acceptance of a tremendous level of expectation. Perhaps even an amount that would be impossible to reconcile with a single videogame.

Torment: Tides of Numenera does meet some of those expectations. Crucially, it nails many of the vital ones; tone, premise, setting. And it gets awfully close with meaningful portions of its narrative. The peaks of its quest design, when characters, theme, and reactive choice all chime together, are superb. That it can’t maintain this incredibly high standard throughout every portion of the game is a shame, but nor is it damning; even Planescape: Torment had its weaker spots. There’s a clarity to the interplay of abilities and stats in Numenera (though too much ease with speech checks), and a refreshing, hand-designed feel to the mechanically straightforward combat encounters.

Sometimes exceptional, always ambitious, and periodically falling short in its aims, Torment: Tides of Numenera is symbolic of the tribulations involved in retreading the path of a long-established creative work. That parts of this game can rival Planescape: Torment in execution means it’s an RPG well worth playing, but, whether due to problems during development or an exhaustion of resources, some areas have not quite lived up to their stated goals.

Further reading: Torment: Tides of Numenera Starting Guide – Hints & Tips for Beginners

Published: Feb 28, 2017 07:59 am