Arkane’s love affair with the back catalogue of Looking Glass Studios is pretty overt, and that’s no bad thing. With 2006’s Dark Messiah, the Dishonored series, and now Prey in their library of releases, the studio are the contemporary champions of the ‘immersive sim’. That genre’s heyday includes lauded classics like Thief: The Dark Project, Deus Ex (designer Harvey Smith is now at Arkane), and, of most direct relevance to Prey, System Shock 2.

There is an actual System Shock 3 in development at Otherside Entertainment (a company with even more direct ties to those Looking Glass/Irrational/Ion Storm years), and if it manages to top Prey as a continuation and tribute to the System Shock ethos then it’ll be quite some game. Despite being stuck with a spare license that Zenimax had lying around (this title shares nothing in common with the Prey of 2006, nor is it anything to do with the cancelled Prey 2), and displaying a shared interest in Art Deco office decor with BioShock, it’s the earlier Shock sequel with which this title shares the bulk of its design philosophy.

There’s also a viewing system called a Looking Glass and a mission called Shipping and Receiving. Yeah.

You are Morgan Yu, sister (or brother, your choice) to Alex Yu, and part of the family-owned TranStar Corporation. The year is 2032, in an alternate timeline where President Kennedy was never assassinated. US-Russian co-operation resulted in rapid progress for the global space program and the creation of the Talos-1 facility upon which Prey is set. There, TranStar is developing ‘Neuromod’ technology, which allows talents like musical or athletic aptitude to immediately be injected into a person. It’s primed for the mass market … what could go wrong?

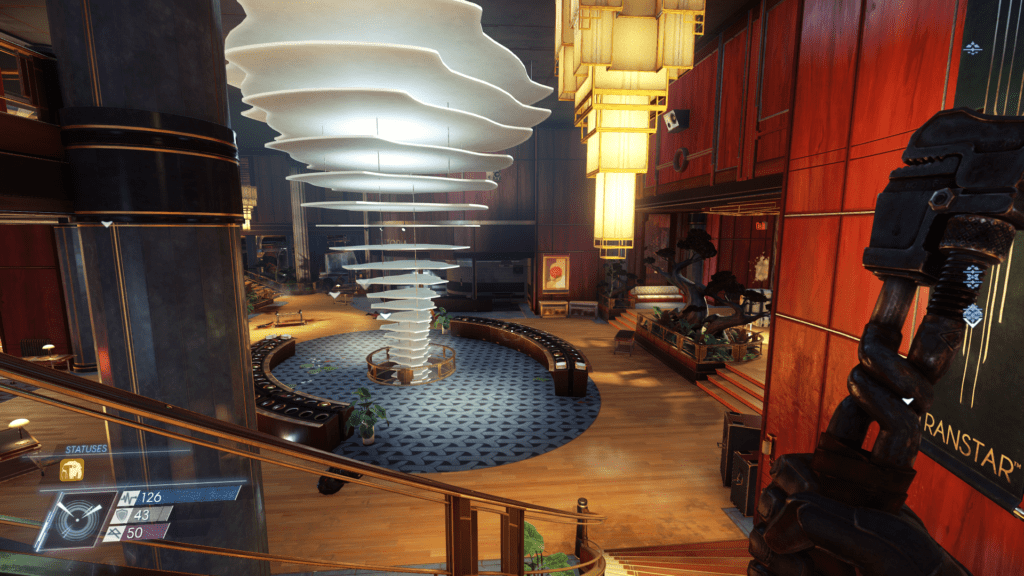

Pretty much everything, inevitably. Within minutes of Prey’s rather clever cyclical opening sequence, vicious Typhon aliens are running amok and most of the crew will be left with nothing but audio logs and embarrassing email chains as their obituaries. What follows is a tense, first-person crawl through Talos-1’s retrofuturist interiors, driven by astute use of scavenged resources, the recurring challenge of how best to use the space and tools at your disposal, and (if you’re inclined) the desire to piece together what exactly happened in the facility.

The primary narrative is an intriguing one, though the main questline tends to double as a method of pushing the player between the connected areas of Talos-1 (the Cargo Bay, Life Support, an Arboretum, and so on), and relies too often on suddenly blocking progression to send you on a tangential mission. Not a bad device, but repeated so frequently here that it becomes a bit predictable.

Like many of its sources of inspiration, Prey shines when the player is off any sort of leash and poking around its interconnected systems and side-stories at their own speed. Happily, this sort of activity constitutes the vast majority of the game.

Talos-1 is one of those wonderful game spaces that’s constructed like a real, functioning (within the boundaries of this sci-fi reality, anyway) space station. Though a little restricted in your movements at first, it’s not long before you can travel between zones broadly at will, either on foot or via a bit of a space walk on the vessel’s exterior. It’s quite possible to wind up somewhere you’re not ‘supposed’ to be, but Prey ultimately doesn’t mind and tends to adapt well to player ingenuity. Quests, and your own curiosity, will bring you back and forth between areas, and your skills and experience will help you uncover new rooms or floors.

For example, early on you may not be able to get beyond a locked door. The most obvious routes inside would be to find the corresponding keycard, or wait until you have sufficient hacking skills to force entry. But you may also be able to smash a tiny section of glass and use your nerf dart crossbow (yes, really) to pop the door release button. Or perhaps create an entirely new path to the rafters using Prey’s excellent GLOO Gun and get in from above. The game gives you tools and systems, then encourages you to learn through experimentation.

Going on little expeditionary detours almost always pays off, either with hidden caches of supplies in hard to reach areas, or weapons and snippets of story you’d usually not acquire until later. Throughout, Prey feels designed with curious, boundary-prodding players in mind.

The aforementioned GLOO Gun is a primary exhibit of this design philosophy. It’s one of the most versatile and liberating tools since Half-Life 2’s Gravity Gun. Useful for traversal, combat, and situational obstacles, the GLOO Gun fires out quick-drying blobs of polymer onto pretty much any surface (but won’t stick to itself). You can widen a narrow beam for an easier crossing, create some rudimentary hand holds to get to higher ground, put out fires, temporarily block sparking electrical outlets, and gum up Typhon foes.

Early in the game the tactic of using GLOO to fix humanoid ‘Phantoms’ in place and battering them with a wrench is standard procedure.

The other early adversaries are the much discussed Mimics; scuttling, headcrab-like creatures apparently made out of the same pulsing black substance as the Pus of Man enemies in Dark Souls 3. They can turn into mundane objects like boxes, piles of towels, or even things like medkits (the bastards), and will happily launch themselves at your face with a screech if you get too close.

While that might sound like an awful series of cheap jump-scares waiting to happen, in-game it comes across slightly more nuanced. Mimic attacks are usual somewhat telegraphed, in the sense that you’ve seen them moving around earlier, or you’ve learned that there’s something distinctly off about two medkits sat next to one another in the middle of the floor.

They also escalate and plateau quite neatly throughout the game. At the point where you might be getting sick of the things, you acquire technology allowing you to identify their hidden forms (points to Prey here for making the scanning tech a bit prohibitive to use, so you don’t just wear it all the time). Just when you’re at the point of casually scanning a room and getting the jump on Mimics with pre-emptive attacks, the game introduces the tougher Greater Mimics who can turn into larger objects and won’t show up on basic scans.

Then, when you’re powerful enough to casually blast Greater Mimics away with a half-aimed shotgun, you’ll have become complacent enough to forget all about the original Mimics. Which is exactly when they’ll start to surprise you all over again.

Prey’s enemy roster isn’t vast, and tends to be derived from the same ‘black goop’ template to some extent, but they all distinguish themselves by demanding a slightly different combat approach. The same device used for scanning Mimics can reveal weaknesses (and, at the same time, gradually unlocks Typhon Neuromod powers), so combat, much like exploration and traversal, involves putting your combined tools to smart use.

One particular late-game foe is supposed to specifically hunt you down. Sadly, this doesn’t quite work because he’s very easy to avoid by simply staying in place for a couple of minutes or leaving for another area. If he were able to cross loading zones, his presence might have matched his billing for intimidation.

Scanning kills your peripheral vision and muffles sound, so you won’t be using PREY VISION the whole time.

The usual pistol and shotgun options are present in Prey, but if you want to get more creative you might invest in the ability to be able to hurl gigantic bits of furniture at opponents. Or perhaps you’ll lure them next to a pipe that’s ready to belch out gusts of flame. Maybe you’ll just lob a dependable Recycling Grenade. That won’t just clear up your problem, it’ll also leave you with some handy materials to turn into fresh ammo or suit repair kits at a nearby Fabricator.

At every turn Prey wants you to engage with its systems in smart ways, without ever outright telling you what to do. It even has a broad capacity to react and adapt to some of your off-map meddling. There’s a point in the game where a useful object can no longer be fabricated with materials due to someone on the station implementing a DRM scheme. This launches a standard side quest to the chap’s office; but if you’ve already been there and used his computer, you would have seen the DRM-implementation in process and may have already stopped it happening.

Many of the game’s most memorable details are in little stories, not even specific side quests, relating to the Talos-1 crew. They are all named, and all have roles and recorded assignments. You will never stumble across an anonymous corpse, but will regularly be able to piece together a crew member’s final moments. Humanising details like emails describing a not-strictly-HR-approved Battlebot league taking place in the isolated bowels of the Power Plant, or even just incidental scenery like a photograph with a face scratched out, are all over the facility.

The broader story plays out like a procedural mystery; what happened on Talos-1 and what’s going on with Morgan Yu him (or her) self?

Pacing, largely player-controlled during the opening couple of acts, gets a bit too hectic at the game’s climax. It begins to usher in floods of enemies, rather than the more thoughtful, creative encounters found during the rest of Prey’s 20-some hour story. A different type of challenge, sure, and one presumably intended to test the reserves of your hoarded resources; but one that’s also inherently less interesting. Prey is never a pure stealth game, but you can spec heavily in that direction and the final few hours rather undermine that option.

No matter how you resolve matters on the station, the ending cinematic is abrupt to the point of being jarring, but a much more revealing sequence follows after the credits. There’s a thematic constant running through the game about the role of memory on consciousness and how it affects the ‘nature of a man’ (Chris Avellone, on writing duties here, revisiting familiar pastures). The ‘true’ ending, while a bit of an exposition dump, does retroactively throw all that preceeded it into a new context, and had me thinking that certain discoveries would have increasing meaning on a second playthrough.

A second run is something Prey actively encourages, both through its tacit desire to see the player use their freedom to ‘break’ the story (this is a game where you can continue after killing your main quest-giving NPC), and the duality of its human and Typhon skill sets.

As noted in my article at launch, the PC version of Prey is sort of the opposite world Dishonored 2; well optimised, but lacking in the HUD customisation options that you’d expect from Arkane. A recent patch is said to have dealt with a nasty save corruption bug (which, luckily, I never ran into).

Some bugs do remain. Sometimes audio logs would autoplay upon being picked up, while other times they’d refuse to play at all (even via the shortcut key) until I collected some new ones. One side quest resolved successfully, then retroactively decided (in a totally different location) that actually it had failed. Prior to this latest patch, certain aspects of the audio were mixed far too high or low, but the update seems to have sorted out the most egregious issues there. That’s for the best, as having some of Mick Gordon’s splendid score all over the place in the mix and the ‘Objective Updated’ noise pitched loud enough for a regular jump scare was rather aggravating.

A special word, too, for Prey’s weird hacking minigame. This seems so cheerfully and self-consciously bad that I’m seriously entertaining the notion that it might be an attempted post-modern commentary on how all these games have lame portrayals of hacking. But more likely it was just jammed into the game at the last minute.

That’s certainly not the case for the rest of Prey’s mechanics, which fit together as interconnected systems with a great deal of thought behind them. Talos-1’s offices, testing labs, and cargo holds have all been designed with player-driven traversal and exploration in mind. Every space has something to reward curiosity, or deft use of environmental objects. What begins as a tense, vulnerable crawl, gradually turns into the confident, resource-rich stride of a protagonist newly at home with their capabilities. Though it’s a slight shame Prey cannot maintain its oppressive tension to the bitter end, twenty hours of that would be pretty grueling; confidence can still breed complacency, and Talos-1 is never truly subdued.

Arkane’s tale of wrench-wielding, audio log sleuthing, and human hubris wears its videogame heritage on its bright red space suit sleeve. Until such time that System Shock 3 may challenge it, Prey is the worthy follow up to System Shock 2 in everything but name.

Published: May 12, 2017 06:27 am