I’m preaching to the converted, but video games are great, right? They let you do all sorts of things you can’t or won’t do in real life. You can go to space, battle dragons, save the world, and drive taxis. The last of which is something a lot of people do in real life, but I definitely won’t. At least I have Neo Cab.

It might not be as common in gaming as gunfights, but from Crazy Taxi to GTA sidequests, we do like our taxis. In 2019, though, the industry has been more about the narrative side of the commercial transportation industry. Both Night Call and Neo Cab concern themselves with the interactions of the driver with the world and the passengers rather than going from A to B, with some interesting results.

Brave Neo World

Neo Cab takes place in a somewhat dystopian, somewhat cyberpunk world – and no, I don’t want to get into a debate on whether it’s pre-, post-, or just regular cyberpunk. While we don’t get any direct info-dumps about the setting, what snippets we get aren’t positive. Racism and classism are still very much a thing, and at least one mega-corporation is absurdly powerful, invasive, and seemingly above the law.

This impacts our poor protagonist, Lina, quite a bit. Lina is a regular human taxi driver in the gig economy. Capra, a mega-corporation, is pushing hard for driverless cabs. And now that Lina’s just moved into Los Ojos – a city that can aptly be described as “Capra central” – human-driven cabs are alternately seen as quaint or dangerous.

What’s worse is that Lina has only just moved to Los Ojos to live with a bestie from her past, and said bestie has now gone missing. Lina is stuck trying to scrape together money to pay for motels and car fuel while simultaneously trying to figure out what happened to her friend. All of this against a backdrop of technocratic institutions, social unrest, and the unblinking eye of Big Brother.

Driving Mx. Daisy

You can see how much car charge a ride will take, but not how much money you earn. Fortunately, it doesn’t really matter.

Neo Cab is billed as a survival game of sorts, but truthfully the survival aspects are minimal. You do need to keep an eye on your money and your car’s charge, but running out of both of these things would require a degree of actual effort. Indeed, as long as you remember to go and visit a charging station, the game largely eschews any real need to think hard about your finances or decisions.

Instead, the gameplay focus is on the conversations you have with your passengers, who are a wild and varied bunch at the best of times. You’ll encounter a bizarre cultist obsessed with a god worm, a non-binary anti-car zealot, a disarmingly friendly back-alley doctor, and a tween star locked in a mech suit for “protection.” Depending on who’s riding, the conversations can be hilarious, insightful, or weird.

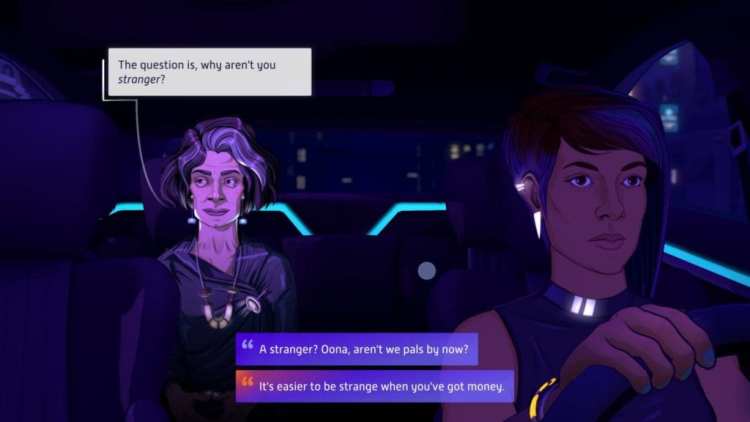

The stand-out is probably Oona, both in good and bad ways. She’s described as a “quantum witch” capable of figuring things out based on alternate realities, albeit through science. It’s a fascinating concept and she’s a fascinating character, who always provides some really entertaining conversations. The problem is that she’s also a bit of a deus ex machina, offering up clues and information that she possesses because of branching realities. I suspect (and hope) there are other ways of getting this information on different playthroughs, but great as Oona is, that method of progressing the plot feels a tad lazy.

FeelGrid Inc.

Still, the FeelGrid system is what makes the conversation system really interesting. The FeelGrid is, essentially, a sci-fi mood ring: It’s a piece of jewelry that reads your mood and displays it to everyone around. This means passengers can tell when Lina’s feeling sad or getting pissed off. Mechanically, though, it means you can’t just pick whatever conversation options you like.

If Lina’s feeling sad, then she’ll be too withdrawn to pick any angry, confrontational responses. Conversely, if she is angry then you might find any and all of the more calming or conciliatory responses locked off. It’s not a complex system but it adds a lovely bit of nuance: Choices you make in one conversation have a (literally) visible effect and will impact every other conversation. Not necessarily in terms of plot, but just in terms of what conversational choices are available to you.

Your choices and decisions have a minor spiraling effect and in a more interesting and fluid way than “X will remember that,” although it’s not one that will ever permanently lock stuff away from you. As with the money system, I feel like more could’ve been done with it, but it’s still a really interesting twist on the standard dialogue tree. And hey, there are a few actual branches in there too.

Neon shine

I’m also rather impressed with the presentation of Neo Cab. It’s most definitely an indie game, but one that uses its resources extremely well. It’s got a deliciously moody look, all dark streets and neon signs, while pulsing synth alternately soothes the nerves or drives the tension. Animation is minimal but effective: subtle shifts of the faces or side glances as the streets roll by. The UI is clean and thematic, considering it’s largely based around your phone. Design-wise, Neo Cab is smashing.

I wish I could say the same for everything else about it, but there are bits that annoy me. Most of the writing is really good, eliciting wry grins and chuckles, but bits of dialogue and a couple of characters are almost painfully on the nose. (I’m avoiding specifics for the sake of spoilers.) And while your playthrough won’t take too long, there’s some repetition involved – especially once you realize that money is practically irrelevant.

Still! For a short, sharp, and occasionally thought-provoking look at a dystopian gig economy, Neo Cab does really rather well. It’s a gratifying burst of gorgeous design, solid writing, and interesting mechanics. I’ve got a nagging sense it could be a little more than it is, but complaining feels a little churlish when what’s here is as enjoyable as it is.

Published: Oct 2, 2019 1:00 PM UTC