It’d be too reductive to hand Telltale all the credit for making episodic adventure-ish titles a viable “thing” for other developers, but there’s no doubt the success of their model has influenced others. Titles made by smaller teams, like The Detail and Prologue Games’ own Knee Deep, have taken something of what is now very much a Telltale ‘formula’ and fashioned it to their own purposes.

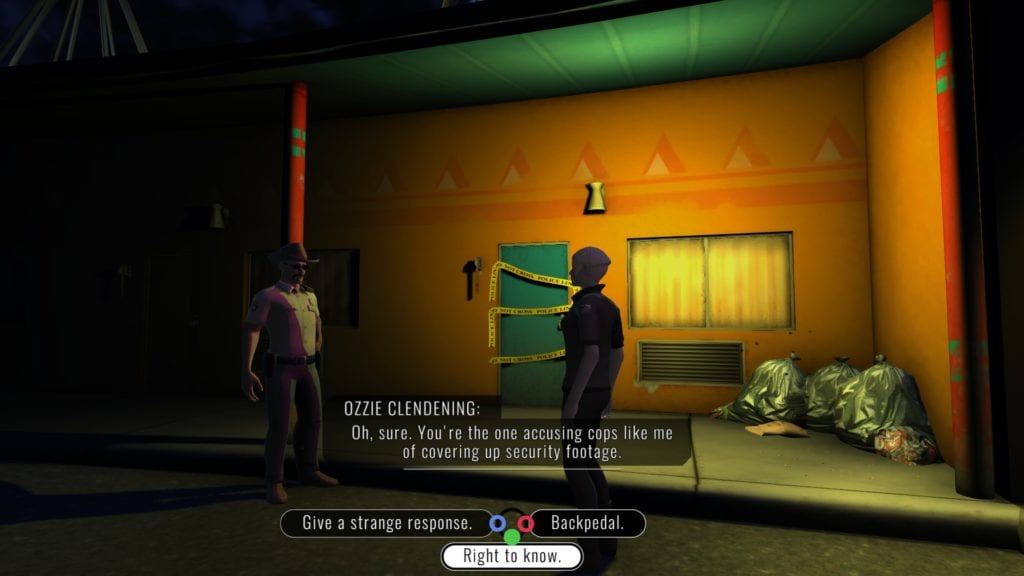

Like latter-day Telltale, Knee Deep’s first act (of three; with a tentative release schedule of late 2015 and early 2016 for the next pair) is less classic adventure game and more visual novel with reactive dialogue choices. But the somewhat guided paths of the game’s three protagonists are explained by a rather novel framing device.

Or, more precisely, a rather theatrical framing device.

In what may well be a Ken Levine-like nod to the illusion of player agency within the frameworks of most videogames, Knee Deep presents its tale as an actual theater production, complete with rotating stage and clever, fold-away prop buildings. On an aesthetic level, this is an interesting approach that I’ve not really seen used before. And, if you want to get all meta-mechanical about things, it also serves as a handy excuse for the restriction on player freedom as they’re pushed from scene to scene.

Nor, surely, is it a coincidence that the unifying factor between all three main characters is an investigation into the apparent suicide of an actor (of screen rather than stage, but still.)

Where the structural metaphor begins to wobble a little is over the matter of dialogue choices. Players do not control their own movements (because the acts of the play already do this,) but are, somehow, improvising the script to some degree. This probably falls under the entirely fair category of “without dialogue choices this wouldn’t be much of a game,” and may get some kind of fuller explanation by the time Knee Deep concludes, but presently feels a little bit incongruous with the rest of the set-up.

Act 1 pulls our three heroes – gossip blogger Ramona ‘Phaedra’ Teague, local hack Jack Bellet, and private detective K.C. Gaddis – into the humid Florida tourist-trap town of Cypress Knee (perhaps loosely named after a real life curiosity museum.)

Has-been actor Tag Kern has (apparently) opted to take his own life in this run-down locale, which is exactly the sort of blog-fodder Teague requires to get back on her editor’s good side. Meanwhile, Bellet is doing his best to pursue the sort of local real estate scandal usually found in Private Eye’s ‘Rotten Boroughs’ section, and Gaddis finds himself drawn into a case that’ll hit uncomfortably close to home.

Knee Deep adopts a fairly ambitious narrative structure, at times hopping forward in time a few days before returning to the ‘present day,’ sometimes with a character-switch along the way. It sensibly avoids too much exposition, instead relying on players to gather certain pieces of information through context, later discussions, or in-game journal pages (for example, a named location or incident may be mentioned in passing, but won’t be overly explained.)

This walks a pretty fine line between a refreshing lack of clunky expository dialogue (“Mrs. Thingy … You remember, our old school teacher from when we were classmates ten years ago!”) and placing a little too much emphasis on players checking their in-game diary pages for fuller descriptions.

For the most part it works, crediting people with enough intelligence and desire to follow the story without it being spoon-fed. At times though, information can be missed or left a bit too obscure. Particularly during the rare (and seemingly random) points where Knee Deep decides to switch scenes without allowing the player to explore the majority of dialogue choices (as it normally does.)

Quite how reactive and influential some of those dialogue choices will be in the long term isn’t going to be clear until later installments are released. Short-term, there are minor repercussions to decisions taken as the various characters, especially as a result of reports filed by the two journalists. It’s nothing spectacular, but if, for example, Bellet has pointed the finger at the not-at-all-an-allegory-for-Scientology Church of We-ists, he might get warned off by his editor. Likewise, when Teague chooses to get too salacious or inflammatory in her blog postings (gotta keep that traffic moving!) it’ll go down poorly with Tag Kern’s friends.

Nothing (so far) appears to have an effect beyond a little extra dialogue, however. Kern’s former girlfriend may tell Teague what she thinks of her, but will still hold a conversation and (as far as I can tell) provide the same information. So although it’s still fun to play along as a belligerent or cynical arsehole (and entertaining to read the ‘worst’ versions of the articles the game periodically asks you to select from,) it doesn’t have as much effect as you might imagine.

This is a shame, because, outside of some Pipemania-ish block-rotation mini-games, dialogue (and article) choices are the main player activities throughout the hour and a half or so that Knee Deep’s first act runs. Again, it’s possible that Gaddis’ penchant for padding his expense claims with dubious items for his pet dog will have some longer-term effect beyond being an amusing running gag. With only one third of the game currently out though, it’s hard to be sure.

Where Knee Deep does deliver is through the long shadows and clever transitional staging of its re-used sets. Character models are relatively simple and express emotion with somewhat exaggerated, Sims-like stances, but their surroundings tend to be cleverly framed to make the most of minimal assets. The characters are also silent, but, rare cases aside, I find no voice acting to be preferable to voice acting on a shoestring. Prologue have smartened up the user interface design since the preview build I saw earlier in the year too, and the game has acquired a suitably sparse and grimy audio theme.

Though it doesn’t yet convey any major consequences to the player’s dialogue decisions, and doesn’t do quite as much as I’d like with its report-filing mechanic, Knee Deep nonetheless manages the noteworthy feat of keeping a multi-character, mystery tale on track through some unique staging and a steady escalation of events. All while pointedly ignoring the crutch of exposition. The story could all too easily have gone missing somewhere between the scene changes and theatrical dressing, but, while it has occasional tonal problems (some of the swerves between darker issues and surreal whimsy like alligators dining on ‘diaper chicken’ are pretty jarring,) the weird narrative is what players of Knee Deep will be coming back for in the game’s concluding acts.

It’s an imperfect opening chapter, and on the expensive side at $25 for the full Season, but I can’t fault the ambition behind telling a noir-inspired story in such an unusual manner.

Published: Jul 11, 2015 03:22 am