It’s a tad unfortunate that Inside had a week-long ‘exclusivity’ period on the Xbox One before making it over to the PC. That’s not a sentence motivated by weird systems-patriotism, but by the desire for people to play it unspoiled. Aside from a couple of brief E3 trailers, I went in knowing very little about Playdead’s first title since 2010’s Limbo; and I’m relieved that was the case. The game won’t be outright ruined if you learn about certain sequences ahead of time, but going in blind is definitely to be recommended.

All of which makes this reviewing lark that bit harder. Tell you too little, and the piece is a waste of time. Spill too much, and I’ve negated my own first paragraph. So, avoiding too many references to individual scenes or specifics of clever puzzles, here’s how and why I think Inside is so successful in its design.

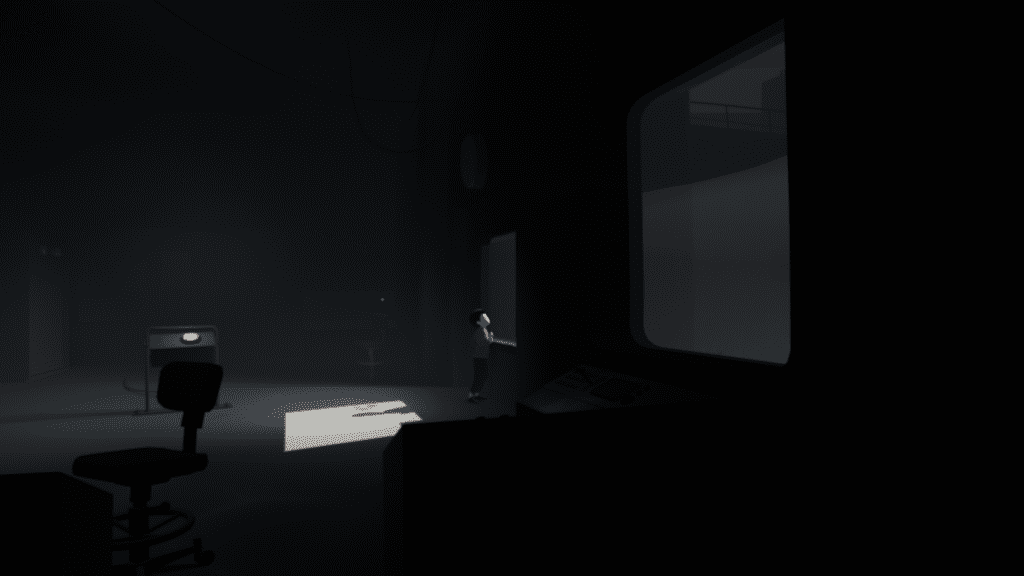

Inside’s colour palette is more expressive than Limbo’s monochromes, but Playdead have absolutely revisited the contrasts of light and shadow found in their first game. The angular shadows, cast predominantly in dark blues and greys, contribute to the bleak, oppressive atmosphere found within the game’s abandoned industrial facilities and flooded silos. Some of the framing is straight out of German Expressionist-inspired film; titles like M or The Night of the Hunter. Compare the image above to this still from the latter film, for example. It may also be no coincidence that both of those films share a theme of pursuit (and endangered children) with Inside.

The young, red-shirted protagonist is always fleeing from danger, and, like Limbo, almost always travelling from left to right, overcoming obstacles through manipulation of the environment (both inanimate, and semi-animate). Here, again, there’s a certain amount of mechanical kinship with Playdead’s prior title.

As well as appealing directly to my heart with lighting straight out of Film Noir, Inside is a fine example of contextual teaching and use of environmental clues. This game has no UI or HUD, nor any on-screen text or dialogue. Instead, it uses character animation, audio, and intuitive object placement to communicate information to the player. Within moments of starting the game within a damp forest, you hear the distant bark of a dog and idling engines. As you approach the vehicles, the boy’s stance changes from one of flight to one of caution. In combination, the wordless message is clear: these men are to be avoided.

Not all games can realistically be expected to convey their information in this manner (trying to learn a hypothetical Crusader Kings III without a UI or tooltips is … not a pleasant prospect), but Inside is a prime example of placing warranted trust in exposition-free instruction.

That elegance of design largely extends to the tight pacing of Inside’s puzzles. This area also sees some good use of intuitive environmental clues, but impressed me even more with its willingness to avoid dwelling on any particular puzzle type. You’ll learn a puzzle-solving strategy, and then maybe only use it once or twice more; sometimes never again. Several times, Inside introduced me to a puzzle ‘type’ that could feasibly have extended through its entire 3-4 hour length. That never proved to be the case, which made for a game capable of springing new logistical challenges all the way to the end.

Some (by no means all) of the obstacles and puzzle constructions are echoes of those found in Limbo. Where Inside does certainly differ, however, is in the frequency of unavoidable deaths. Limbo gestured towards the idea that it warned players ahead of vicious environmental hazards, but in reality (unless you were some kind of reactions wizard) most players would only learn through trial and error. Inside is much closer to the model Limbo seemed to be aiming for. You get more chance to react to threats, correct your actions, and avoid a grim demise.

That won’t always be enough to save you from depictions of death that are often even more disturbing than Limbo’s gory, black-and-white abstractions. Inside does not shy away from extending the stark cruelty of its world to its stylised, young protagonist. That’s appropriate for the setting, but the narrative justification doesn’t make it any less distressing to witness.

That narrative itself is as hands-off as the contextual communication of controls and actions mentioned above. Without any form of written or spoken exposition, everything you glean from the story has to earned by paying close attention to the surroundings. You’ll most likely be revisiting scenes, background figures, and details in your mind long after the credits roll, attempting to piece together theories. Inside provides you with enough detail to convey a broad picture, but digging deep into specifics (and I believe there are certain specifics to be found, even if Playdead may not subscribe to the idea of a 100% ‘canon’ storyline), will take some serious musing.

Without revealing anything specific, the ending made me feel both guilty elated and horrified at the same time. It, like the rest of the game, benefits from exemplary sound design. Inside takes a sparing approach to music, and what little there is tends to be eerie, unsettling drones. Much of your time in the game is spent alone, and this sense of isolation is only heightened by the reverberating footfalls in abandoned industrial buildings. The consuming, ear-drum squeeze of a flooded hallway. Or the crash of a cage from rafters to floor.

A few words too about the PC version, which runs at a smooth, capped 60fps and provides a scattering of basic options like resolution and brightness. While the graphics options are as minimal as the rest of the game’s attitude to text, you can freely rebind all the keyboard controls. That’s for the best, because the default arrow key movement set-up is a bit rubbish. I played with both keys and a basic 360 gamepad; both of which were equally fine for a game of this nature. Inside appears to make use of Denuvo DRM, which is something you may wish to know if you’re opposed to that sort of thing.

Inside exhibits a consistency and obsessive attention to detail that few other games can boast. It’s a tight, fraught four hours of oppressive pursuit, smart environmental manipulation, and unsettling imagery, presented with incredible care. The animation (particularly of the young protagonist) is terrific, and does so much to aid the contextual prompting the game uses in place of written or spoken exposition. Bleak though much of it may be, there’s real beauty in the title’s clear homages to Noir/Expressionist lighting techniques, and an audiophile care to the splendid sound work. Not many games released this year will possess such coherent artistic vision and satisfying sense of design.

Published: Jul 8, 2016 11:45 pm